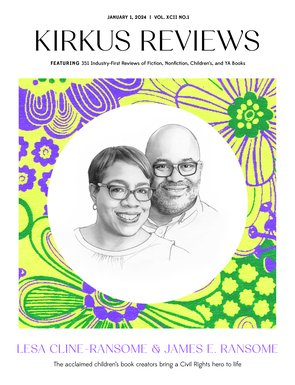

Imagine a man who once said that he was incapable of feeling love for his infant daughter, and asked a friend if they’d be willing to adopt her. Now imagine that this same man repeatedly cheated on his wife. Finally, imagine that he also headed a military project that directly led to deaths of at least 110,000 people—and possibly as many as 210,000. A $100 million biopic has been made about this very man—one in which he’s surprisingly not the villain, but something resembling a hero. That film is Oppenheimer, based on the Kirkus-starred, Pulitzer Prize–winning biography American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. It’s written and directed by Christopher Nolan, stars Cillian Murphy, and premieres in theaters on July 21.

Murphy stars as J. Robert Oppenheimer, a University of California, Berkeley, physics professor (known as “Oppie” to his students) who directed the Manhattan Project’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the first nuclear bombs were designed and built, later to be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As the head of the scientific project, he became widely known as “the father of the atomic bomb.” As depicted in Bird and Sherwin’s impressively detailed biography, and in Nolan’s film, Oppie seemed to have few qualms about the bombs’ use until after they were dropped on Japan. Then he did try to do everything in his limited power to make sure they wouldn’t be used again—but it’s very hard to call him a hero, exactly. He reportedly told President Harry Truman, in an exchange included in the film, “I feel I have blood on my hands.” He did, of course—and so did Truman and everyone else involved with the bomb. One can make the case that dropping the bombs was necessary, of course—but one can also make a very convincing case that it was a war crime.

Nolan tries very, very hard to make Oppenheimer seem sympathetic; in a few scenes, Murphy is stares nervously into space as Oppie has vivid, nightmarish visions of blinding flashes, blistering bodies, and charred corpses—although there’s no evidence that he ever had such visions. In reality, Oppenheimer was the man who gave very specific instructions to the military on how best to deploy the bombs to inflict maximum casualties. But, hey, he did feel bad about it later, Nolan seems to say.

In any case, by the 1950s, the hawkish head of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss (played as a villainous caricature by Robert Downey Jr.), felt that Oppenheimer—who’d known several active members of the Communist Party USA over the years, including his brother, his sister-in-law, and his lover—should lose his top-secret security clearance. The AEC’s hearing takes up a good portion of the film, and apparently the audience is supposed to care about this; Oppenheimer’s reputation is on the line, after all. However, the film elides the fact that Oppie had already named names to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1949—informing on several of his own students.

Murphy does his best in the title role, but he can’t muster any of Oppie’s fabled charisma, which made him a popular professor and, indeed, a natural leader. Instead, Murphy’s performance is twitchy and awkward, as if he’s trying to summon up deep feelings from a void. Somewhat better is Matt Damon as Gen. Leslie Groves, the Manhattan Project’s military director; his no-nonsense, all-business performance make Murphy’s look positively strained.

There are plenty of impressive actors in the cast, in fact—but very few women, and Nolan has great difficulty making any of them into living, breathing human beings. Emily Blunt, for instance, plays Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty, and the script allows her to be drunkenly annoyed at her husband or her husband’s tormentors, but little else. Nolan doesn’t seem interested in portraying her as a complex person with a rich history, which she certainly was, as a German-born botanist and former Communist Party member who’d married several times before; one of her former husbands, a union organizer, died fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Nolan’s script disposes of all this in a few lines, before hurrying on to more of Oppenheimer’s angst.

Florence Pugh, a fine actor, is unfortunately wasted as Jean Tatlock, a Communist activist with whom Oppenheimer had a brief relationship, and, later, a brief affair while he was married to Kitty. Viewers learn that Tatlock hates romantic gestures: She tosses Oppie’s bouquets into wastebaskets, for instance—a quirk that Nolan repeats to signify a whole personality. One also gets the impression that Tatlock spent the majority of her life in the nude, judging from Nolan’s portrayal; in one scene, Tatlock makes Oppie translate a famous line from the Bhagavad-Gita from the original Sanskrit—“Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”—aloud, in the middle of a sexual encounter. (In real life, Oppenheimer quoted this line to an interviewer—no intercourse involved.) In a bizarre fantasy sequence, Tatlock and Oppie go at it as he sits in a chair being grilled by the AEC hearing board—while Kitty stands by, consumed with jealousy. It’s as if a few pages of erotic Oppenheimer fan fiction suddenly slipped into the script.

Florence Pugh, a fine actor, is unfortunately wasted as Jean Tatlock, a Communist activist with whom Oppenheimer had a brief relationship, and, later, a brief affair while he was married to Kitty. Viewers learn that Tatlock hates romantic gestures: She tosses Oppie’s bouquets into wastebaskets, for instance—a quirk that Nolan repeats to signify a whole personality. One also gets the impression that Tatlock spent the majority of her life in the nude, judging from Nolan’s portrayal; in one scene, Tatlock makes Oppie translate a famous line from the Bhagavad-Gita from the original Sanskrit—“Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”—aloud, in the middle of a sexual encounter. (In real life, Oppenheimer quoted this line to an interviewer—no intercourse involved.) In a bizarre fantasy sequence, Tatlock and Oppie go at it as he sits in a chair being grilled by the AEC hearing board—while Kitty stands by, consumed with jealousy. It’s as if a few pages of erotic Oppenheimer fan fiction suddenly slipped into the script.

Are viewers supposed to see Oppenheimer as a man of great passion? Who knows? But it’s clear that Nolan is doing everything in his power to try to distract the audience from the stark fact that his protagonist shares responsibility for one of the most horrific events in human history. Bird and Sherwin’s exhaustive biography, by contrast, doesn’t try to emotionally manipulate its readers, and it portrays the women in Oppenheimer’s life as actual people. They stick to the facts and let readers draw their own conclusions. One can only hope that their book will serve as the standard portrayal of Oppenheimer in the popular culture, and not this big-budget film. Don’t count on it, though.

David Rapp is the senior Indie editor.